Providing optimal nutrition to children with cerebral palsy (CP) helps improve their nutritional status and their overall general health.1

Quite often, children with CP require specific nutritional interventions. Indicators that can help you determine if the child is in need of a nutritional intervention include:2

- No weight gain or growth

- A deviation from an established “growth pattern”

- Low body fat-stores with low weight in respect to height or length

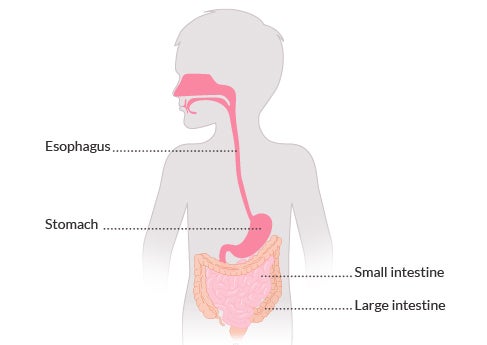

- Prolonged or stressful oral feeding

- Signs of pulmonary aspiration or dehydration

- Evidence of micronutrient deficiencies

Once you identify the medical need, remember that caregivers play an influential role in providing the recommended nutritional solution. In fact, children with CP are very dependent on the caregivers’ understanding and application of your recommendations.1

The more you communicate with caregivers, the higher the chances of a successful nutritional intervention.

In the following section, we will provide you with helpful information related to both the nutritional assessment and the nutritional recommendations for children with CP.

The choice of a nutritional strategy, as well as the mode of administration, depend on:2

- The child’s nutritional status

- The child’s nutritional requirements

- The child’s ability to consume adequate quantities of food and fluids orally

- The risk of pulmonary aspiration

Before recommending a nutritional strategy, nutritional requirements need to be carefully assessed. Several specialists may take part in this overall assessment to help determine the best nutritional strategy. It is critical to include dietitians and speech & language therapists as part of the team, in order to provide a complete nutritional solution.

Nutritional requirements vary depending on physical impairments, feeding difficulties, body composition and physical activity levels.2

In order to calculate the estimated requirements for energy and nutrients, it is recommended to individualise energy based on ideal body weight for chronological age (10th-25th percentile) in the malnourished child and on multiples (1.0-1.2) of the resting metabolic rate in obese children.

Anthropometric assessment is the first step needed to calculate energy requirements. Preferably, weight measurement should be obtained on a digital scale; but, if the child is unable to stand, the use of a wheel chair scale is recommended.3

The height of children younger than 2 years of age or unable to stand should be obtained through reclining length or through segmental measures.3

For body composition, the best way to estimate it is via the DXA (dual energy X-ray absorptiometry). When this is too expensive or unavailable, skin fold thickness and bioelectric impedance are suggested.3

→Take a look at our online assessment tool that can help you in the anthropometric assessment of children with CP (download the pdf version here).

It is advisable to routinely measure and monitor the weight, height and body composition of children with cerebral palsy, in order to adapt energy requirements accordingly.3

Following clinical assessment, the child’s nutritional needs should be discussed with the caregiver.

Caregivers may have questions or doubts about the new nutritional strategy, and it is important that you fully explain the reason(s) why their child needs special nutritional support, how to make things work and who can help.

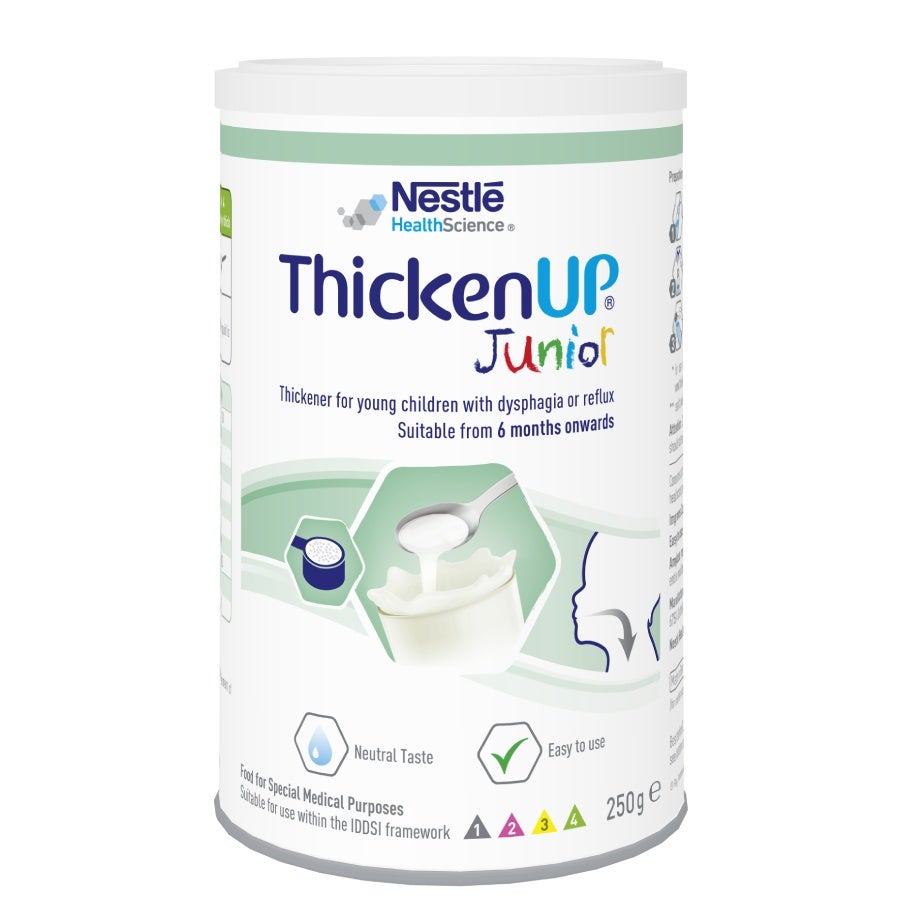

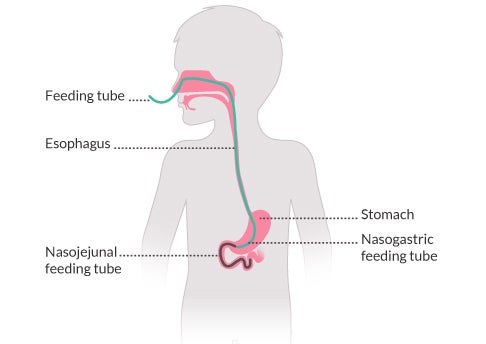

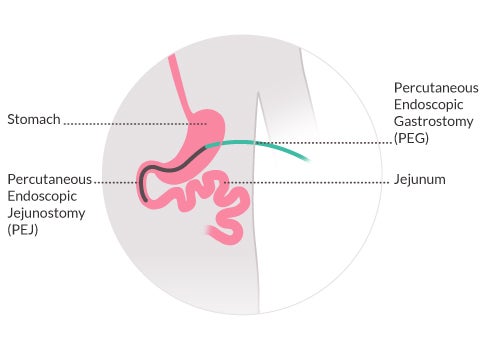

Introducing thickeners or oral nutritional supplements (ONS), while ensuring adequate position and physical support during meals, is usually the first approach.2 If, despite these strategies, the child is not gaining weight, then more advanced solutions need to be considered, such as gastrostomy.

We will cover each nutritional strategy in the following sections.

References:

- Verall TC et al. Children with Cerebral Palsy: Caregivers' Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2000;61(3):128-134.

- Bell KL and Samson-Fang L. Nutritional management of children with cerebral palsy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67 Suppl 2:S13-6.

- Scarpato E et al. Nutritional assessment and intervention in children with cerebral palsy: a practical approach. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68(6):763-770.